While I was working on the Goya in the last post, the folks in charge of NGA's Art Around the Corner program came by to ask if I might be interested in doing some sessions with the students in the January session. I was thrilled to accept, because this program is an opportunity to make a real difference in some kids' lives through art. The NGA partners with DC Public Schools to bring 4th and 5th graders into the Gallery several times a year, not just to look at the art, but to participate in artmaking as they learn to see the world through artists' eyes. It is one of the most gratifying experiences I have had as a painter. To learn more about this program and to see it in action, here's a video made in 2011 which shows how it happens: https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/video/art-around-the-corner.html

KathrynLaw

20220406

Art Around the Corner

20220124

Goya, Phillips, Cezanne

20220115

catching our breath

It's a different world than it was when I last posted here over two years ago. The pandemic started, and since I was living in DC (one of the highest rates of infection in the country); being in a high-risk group, I was in hard lockdown for over a year. My painting and teaching at the National Gallery came to a halt, along with everything else. My husband's work also ceased, and we made plans to return to Southern California as soon as we could get vaccinated and travel safely.

Now, after 8 months back in San Diego, we're still at risk despite being vaccinated and boosted, so we are adapting. I miss the work that I loved so much at the NGA: painting, interacting with visitors from all over the world, working with DC Public School Elementary students in the Art Around the Corner program, painting commissions...all gone. My brother very nearly died of Covid (pre-vaccine) but fortunately he survived. Some dear friends did not. Nearly a million people in the US have been lost to this virus. We can't long for a return to normal, because that normal is gone. It's a different world now.

For a long time, making any kind of art was out of the question. For many creatives, this has been a terrible time. I took down my website. I still have all my oil painting materials, but still can't bear to look at them. Instead, what feels hopeful is change...as in every aspect of life. I've dabbled in watercolor over the years--some attempts are posted here--but never reached the level of expression that I wanted in that medium. I always said that I have a love-hate relationship with watercolor: I love it, it hates me. That's about to change.

Now that no one's watching (since I'm not posting), I can really delve into how this medium works and try to find my voice in it. In art school, watercolor was not a medium that got any respect, so we just didn't talk about it. That's okay. Finding one's way in a medium is always personal, no matter how much instruction one receives.

As I find my way, I'll post some exercises here and share experience. First though, I'll catch up a little with some of the last work that I did at the National Gallery, just to close that out. I've documented my painting life on this blog since 2005, so I'll fill in the gap and then, move on.

20191025

Post Emily

I finished working from Portrait of My Grandmother two weeks ago, and there may be some tweaks that I'll add in the home studio but all in all, it turned out very well. This is 36" x 24", and I will post some progress shots below.

20190821

Emily

The lady whose portrait this is, Emily Motley, is the artist's grandmother. She was born into slavery in 1842, and freed when she was about 20. Married a Native American who had also been a slave, and they raised a beautiful, successful family. Archibald Motley Jr. graduated from the Art Institute in Chicago in 1918 and struggled to succeed as a painter, so he worked as a porter on the Wolverine, a train from Chicago to Detroit. His father was also a porter on that train, one of the best jobs available to African Americans at that time. Motley could not afford to buy quality art supplies, so he used a canvas laundry bag from the train as a support for this painting. This explains the extraordinary texture, which I'll talk more about as I work. He struggled for a long time to finally become successful as a modernist, totally different style, but his portrait and the other one of his grandmother are his finest work IMO and they were his favorite paintings. She was about 80 when this was painted in 1922.

I highly recommend the supporting material on the NGA website, with videos that really expand on one's understanding of the importance of this work. Curator Nancy Anderson's talk is absolutely wonderful, providing essential context and enlightenment about this work.

The other painting of Emily is the richly symbolic "Mending Socks", 1924, which is in the collection of the Ackland Museum in Chapel Hill NC. I had the opportunity last month to view that work and the curatorial file, which is filled with articles, interviews and documentation relating to both these works. I'll have more to say as my work progresses.

20190629

Progress, and old business

20190622

Back to Work

Here's the start of day 1 and the end of day 2:

My canvas is 20 X 24". Still a long ways to go, many corrections and layers to add.

Kenyon Cox was a very important painter, illustrator, and muralist in the Academic Classical style. He trained at PAFA and in Paris. This landscape is an early work in his oeuvre, a bit looser than his later work. He taught at the Art Students League, where he applied the ancient dictum "Nulla Dies Sine Linea"--no day without a line (of drawing), still the best advice for artists of all kinds. There are a number of his drawings in the NGA collection as well.

The painting has a buff-colored ground and no overall undertone. It seems constructed of many thin layers built up to portray the lush softness of the grassy fields and the trees. That's my strategy, to get the soft, subtle glow of gentle color coming through. The biggest challenge is to tone down my usually-brighter palette without killing it. Landscape is definitely in my comfort zone, and Kenyon Cox has a lot to say about it.

20180721

Rembrandt and Vermeer, finished

The Vermeer which was begun months ago is finished as well, I blogged about it before here. The final painting and some detail shots are below.

Details ("open link in new tab"):

If you missed the earlier post, there is a lot of great information about the meanings of these objects here. The symbolism has been debated for centuries, but even just the literal meanings of these objects are fascinating. The bread basket was hung on the wall to keep the bread away from mice. The dark object above that is a framed picture. The footwarmer on the floor has been interpreted as sexual metaphor (heat under the skirt), especially given the Cupid tile next to it and her bare arm, but it was also a practical fixture in daily life.

20180526

Rembrandt in Progress

We do not know the identity of the sitter, it hangs side-by-side with this portrait, and it seems that this pair of portraits might be husband and wife. Rembrandt made many portraits of wealthy Dutch people who are not known to us now. This pair of portraits has a very interesting provenance involving the Yusupov family, surviving both the Napoleonic invasion of Russia and the Bolshevik revolution. The paintings were taken off their stretchers, rolled up and smuggled out of Yalta aboard a British ship. They are now part of the National Gallery's permanent collection.

I'm three sessions into the Rembrandt, and the work is coming together. It's a difficult painting to work from even in person, because the dark parts are very dark. It's not due to old varnish, this painting had a complete conservation in 2007; but the contours in the drapery have darkened to near-imperceptibility. My guess is that Rembrandt used lead white as a lightener to describe the folds, and that has now darkened and become nearly as black as the areas around it. The high-res image on the NGA website is actually much better, because it was taken under very bright light which reveals more of the contrast than can be seen in person. Another very interesting fact about this painting is that it was transferred from one canvas to another (not relined, actually transferred) by a Russian conservationist during the 1800's. It wouldn't seem even possible, and is not a method that modern conservation would employ (since all modern conservation measures MUST be reversible), but it was commonly done then. Here is a link about the process to transfer a painting from one support to another, among the riskiest procedures ever used. Here's a link to the technical notes about this specific painting.

Work in progress, 24" X 20". Excuse the glare!

20180525

Vermeer and Duchamp

The Vermeer is a huge challenge, especially because I can't work from the original which is in the Netherlands. So, I requested a high-resolution image and information from the Rijksmuseum, which they very kindly sent. This link is a wealth of information about this painting, Vermeer's masterwork, which is full of symbolism and sublime beauty. When I took it on, I didn't realize how much difference it would make that I couldn't see the actual work. The authoritative image is only as good as the monitor with which one views it, so I loaded it onto several computers and tried to sort of "average" the color interpretation.

Here is the work in progress, probably 2-3 weeks from being finished, lots of adjustments and details to be done:

20180211

Pope Innocent X

Here is the almost-finished painting, in front of the original:

We must use a larger or smaller support than the original. Since there are other references in a larger format (see below), I chose to go bigger (24 x 18), and the proportions are a bit different.

The original and the details of it can be seen on the NGA website, here. This painting was bought by Andrew W. Mellon in 1930 as an original Velazquez, but scholars have since established it as "Circle of Velazquez". Velazquez painted the full size portrait of Pope Innocent X in Rome, here is an image of that:

20171216

Lievens nearing completion

Up close, there is still quite a bit to do. We must keep the materials at least 4 feet from the painting, so adding a couple feet for the distance to my eyes, I'm actually about 6 feet away while working. From that distance, my copy looks amazing; but then I step up close, and the perfection in the original makes me want to hang up my brushes.

Lievens did quite a few paintings of this same model. Here are some links with images of other "tronies". I think it had to be the same model.

Sotheby's and Christie's

The magical part of copying a work is not knowing how some of the effects were created, then accidentally stumbling onto those methods while working. Like happy accidents, those "ah-ha" moments are what make the exercise so valuable.

20171215

Portrait project 4

Here are two portraits of the same sitter, and a story to go along with them. I'll start with the one that I feel best captures who he is.

20171202

Lievens in progress

Last week, my husband took this shot of me working on my Lievens copy. Made good progress this week, starting the eyes and some of the skin tones:

The eyes, even unfinished, have brought the figure to life. Visitors love that, and for good reason. It's much easier now to envision the whole face. There is still much to do, probably three more sessions. I'm reserving the beard for last, because that seems to be the order that Lievens followed. The paint and scoring that make up the "whiskers" clearly overlap the skin and clothing.

I am using only an earth palette. Although I brought chromatic primaries with me, I didn't touch them. The "blue" eyes are painted with black and white, which is almost certainly what Lievens did. In isolation the color is grey, but in the warm context of the skin, they look very blue. Other than that, I'm using yellow ochre or raw sienna, earth red, burnt sienna and burnt umber. As for painting medium, I would love to use Venice turp which would give a lot more traction especially for the thicker passages of the skin, but real turpentine is not allowed in the NGA because of the stronger smell. Walnut alkyd medium works great for the glazing, adding translucency and a hint of tack and traction.Walnut oil is a nod to the original, since these masters were thought to use walnut rather than linseed. The alkyd helps it dry much more quickly than walnut or even stand oil would, alone.

If you haven't listened to the NGA podcasts about Jan Lievens, there are links in this post. Here is a slightly closer view of the copy at the end of the day:

20171118

Portrait Project 2 & 3

20171117

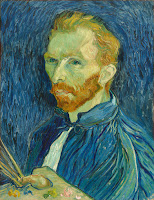

New Copyist project: Jan Lievens

My next project is pretty much the other end of the spectrum from Van Gogh. Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was a contemporary, friend, rival, and studio-mate of Rembrandt. He was very successful during his lifetime, but fell into relative obscurity afterward for various reasons. His work is incredibly luminous, like Rembrandt's, and in fact much of Lievens' work was attributed to Rembrandt for some time. Finally emerging from Rembrandt's shadow, Lievens has gotten the credit he is due.

In 2008 the National Gallery mounted an exhibition devoted to Lievens, and produced three 8-minute podcasts which are still available online. Listen to them here:

https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/audio/liev-wheel1.html

https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/audio/liev-wheel2.html

https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/audio/liev-wheel3.html

Here is a self-portrait from about age 20, when he was considered a prodigy: